In a multi-month period of trying to train while dealing with a long injury, I’m faced by all kinds of questions. Dark questions. Desperate questions.

-What if I can never run fast again?

-What if the most fun races will forever be off-limits?

-What if it’s never gonna heal? Should I quit running altogether?

Those are understandable questions. They pop up subconsciously. In my case because of an injury that prevents me from doing the serious training I’ve quit my job for. Maybe you’ve been in a similar situation. You’ve designed a great new product, but it just won’t sell. That new feature of your script you can’t get to work. Doing job interviews but you still haven’t found one, your new project that just doesn’t seem to gain traction. So there come the questions. They eat up our energy, they lower our moods, they make us doubt, or even worse: lose hope.

160k training weeks I had in mind never happened

But those questions aren’t helpful. After a time of mounting despair, I thought that being stuck was bad enough without those energy-draining questions. Even when we’re right in asking such questions, they will not move us any closer to our goals. Wouldn’t it be better to drop them? Thinking about this, I wondered: if difficult questions can bring us down, could there also be questions that lift us up?

“Sometimes we need better questions”

And then I remembered an idea I’d heard podcaster Tim Ferriss talk about. Whenever facing a project that had become a grind-fest: hard work deprived of fun, he started wondering: “what would it look like if it were easy?”. He’d then start simplifying. In the example of training to stay fit: maintain basic fitness by doing only the most simple exercises, that require the least amount of gear, can be done entirely from home, etc. I love this way of thinking because it reduces negativity. So I considered a different version of the same question:

What would it look like if it were fun?

I started asking myself this question. The following days my subconscious came up with various ways to have fun despite of the injury. Ideas that got me fired up, adventures I was immediately looking forward to. So I took out the calendar and started planning. After all, the constraint of not being able to do long or fast runs didn’t mean it was impossible to have any fun at all, right? What about running to visit a concert/museum and then run back? Plogging? Pushing boundaries or running in challenging territories?

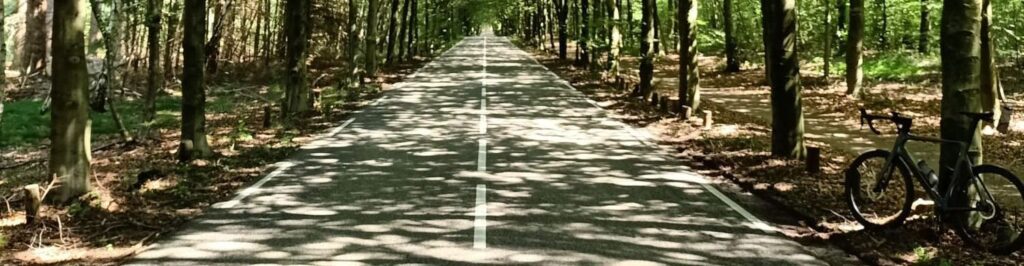

I decided a good start would be to schedule my longest bike ride ever, to pass the 200km-mark for the first time. Challenging a limit gave me energy. Breaking that barrier proved not only possible, but highly enjoyable. And it led to micro-adventures including asking for water in a garage along the way and chatting with a complete stranger who crossed paths for some time. I’m already looking forward to the next adventure. It’s one small question, but it made one big difference. And then I thought about taking the question one step further.

What would it look like if it were epic?

Doing epic stuff makes you feel cool. I don’t know the exact ingredients that make something epic, but the word ‘unusual’ is surely a building block. What is an unusual act that would impress yourself? That might just be a good antidote to that bluesy feeling of being stuck. During that 200km ride I thought ‘what if I broke this limit, and did it again tomorrow but then a bit more?’ That sounded epic, or at least fun. So I did exactly that: biked past the 200km barrier, did it again the next day only then I ran 5k immediately upon coming home. The rides were very hot and not without obstacles. But boy, did this make me feel good!

Minor obstacles:

-shoe plate got so hot it twisted, tearing through the sole

-saddle accidentally dropped an inch in height whilst cycling

Now it’s not about the numbers, and other people’s limits are higher or lower or in completely different areas of expertise. And this lesson isn’t about injuries, cycling or running at all. The experiment in this example taught me that it is sometimes possible to trade our demotivating questions for empowering ones. And better questions lead to better answers. Or at least to a lot of fun!

What’s a question stuck in your head that doesn’t move you forward?

Can you think of a better question to ask yourself?

References:

-Tim Ferriss. The mentioned question comes up in a number of his podcasts and I believe in one of his books. Valuable reading/listening, because more context is provided there. Tim also mentions it here in questions that changed my life.

–Strava log of the first 200km ride

Leave a Reply